Wired and The Golden Age of Free Speech

In its 25 year history, Wired Magazine has sought to define the influence that technology has on our lives in progressively innovative and radical ways. From Barack Obama to Edward Snowden, Serena Williams and Elon Musk, its ongoing mission in the service of design, politics and the arts has held a flame to traditional media formats, leaving other publishers in its dust.

Creative Director David Moretti has been responsible for over ten years of this change, credited with establishing Wired’s Italian outpost on behalf of publisher Condè Nast before moving to San Francisco to head up the creative team in the US. We went behind the scenes of the February issue, The Golden Age of Free Speech, revealing much about one of modern publishing’s most influential figures in the process.

Wired is a finalist for the 2018 ASME awards for General Excellence in Design, and for the November 2017 cover story “Love in the Time of Robots”

You’ve been on an enormous journey to where you are now as Creative Director of Wired U.S in 2018. Can you introduce yourself and how you came to be here?

Well, my name is David Moretti. I'm a designer with a background in history, a professional journalist and a super-geek. This mix of passions and education helped me a lot in the publishing scene; to be a designer and talk with designers about communication while speaking with editors about journalism, and as a historian I work with the company to strategise the brands’ expansion and ideas in a different and precise way.

I first subscribed to Wired in 1994 — part of the original fan base, if you will. I'm originally from Italy and started out as a designer, where I launched the Italian version of Wired with its first editor-in-chief. We were hired to create a special department at Condè Nast Italy. It was 2007 and so everything was changing. ‘Print-only’ had no logic to exist as a strategy for a publishing company, but traditional media owners were not prepared to imagine the future being packed up in the technology of the time. So Condè Nast Italy tried to create this department that was able to work in different directions: from web design, app design, events, video and of course traditional publishing mediums like magazines.

And one of those projects was Wired…

The challenge was to launch a magazine some 15 years after it was established in the US. We didn’t look at it like a magazine, instead investigating the possibility of launching a brand while thinking about how important Wired was for digital culture. It's not a magazine about technology, it's a magazine about the culture around technologies and innovations. We thought about the social need for a brand that can collect and meet great expectations.

At the time we faced a very deep cultural, political and economic crisis — it was the peak of the Berlusconi era. We discovered a lot of people, particularly the younger generation, had a tendency to study and leave the country, while the media were more interested in promoting Italians as stereotypical football players and models. We decided to launch Wired Italia using the unknown and the excluded and turning them into the protagonists. Condè Nast is based on titles like Vogue, GQ, W and Glamour. When we came up with the idea of putting unknowns on the cover they were shocked and not completely convinced. But we became a phenomenon because we covered a world that was not interested in mainstream media. Again, we didn't start with a magazine, we started with a conversation.

I became Creative Director at Wired Italia the same year that [former Wired Editor-in-Chief] Scott Dadich become Creative Director of Wired U.S, and we developed a close relationship. He was always curious to see how you could define something that was 100% Wired, but at the same time 100% Italian without mimicking the American vernacular or style. He was also interested in the natural way to play across platforms. When he became Editor-in-Chief he called and asked "Would you like to join the team? We want to do what you did with Wired Italia. We want to have an holistic strategy and a holistic view for the brand.” So, I joined the team, as deputy creative director, working with head of creative Billy Sorrentino. That was three years ago. A year and a half ago, I became Creative Director.

The scale was so different. In Italy we were a punk rock band. The workflow was like rehearsing in the basement where we could react to anything. But then I moved from a team of 15 people to a team of over 100 here, and it’s not only San Francisco but New York too. Everything needs to be planned in advance, the machine needed to be perfectly oiled.

Wired's San Francisco Headquarters, designed by Gensler (who also designed Dropbox's Australian office).

Wired was, in many ways, still a traditional print magazine at the time too. For example, the office was literally divided into different areas. The website editors sat on an entirely different floor from the print magazine editors. Scott physically changed the place and merged departments so the video, print and digital teams all came together. Now, for me as creative director, it's impossible to say I have ‘print designers’. There are no more print designers because the same person that is involved in print now oversees special features online, and might direct the video team in creating short videos with animation and so on. They’re responsible for the visual communication strategy across all platforms, including working on a daily basis with our social team.

How many people sit on your team in the US?

Between the photo department, design department, which includes print and digital… that’s 20 for sure, and if you add in the video and social teams (we are hiring for new platform designer positions there now) it is around 30 people.

How then do you approach the creation of an issue amongst that team?

First of all, the workflow is completely different to how it used to be. The creative process needs to include a cluster of possibilities — video, print, web, social — which will influence which artist we are going to involve and on what platform it will work. Previously, the magazine was primary and that set the direction of everything. That was a mistake, or we realised it wasn’t optimal because every platform stands for a specific experience. The magazine is immersive, there is a tactile experience and a way to consume it, ‘the leap through’ which is one-directional. But Wired might want to mess with that. For example, in our issue guest-edited by Christopher Nolan, we created wormholes to navigate between different pieces. Video is immersive but stands on a completely different logic. You need to take away all the possible barriers between the content and the user because of the medium itself and the reaction that you have to it, the way you click, etc.

Wired’s issue guest-edited by Interstellar/Dunkirk-director Christopher Nolan

Design plays a different role too. In the magazine, design is part of the content itself. Not only does it define the frame, but it can suggest an emotion. It can involve you. It can provoke in you a specific reaction, or an emotional reaction. Here at Wired, we pay a lot of attention to that. Why? Because Wired is a magazine that doesn't just inform but communicates. Information and communication are two completely different things. To inform is to seek specific information. To communicate, it’s more than just the information, it’s the experience. If I want to communicate with you, I say words, but I also I move my hands; my face might change expression. I use so many signals to communicate what I'm saying. Communication is an emotional experience, and is about so much more than just words. Communication involves a dialogue between two subjects. So, my goal at creative director, is every day I want to communicate with our audience that we are Wired. The goal for me is having a person read the magazine say, ‘I knew it. It's Wired.’ We don't drop the truth from above. We are part of our community; we are in dialogue.

You briefly mentioned expectations, and Wired has built a brand from constantly raising the expectations of its audience. How do you ensure you and your team are constantly surprising people and living up to what they believe the magazine to be?

At Wired, the content is king. This is something that I spoke about with our Editor in Chief, Nicholas Thompson, when he started at Wired in 2017. There is no designing ‘for design.’ There is design for communication. Take our October 2017 cover story about Blade Runner: 2049 as an example. Blade Runner is simply one of the most important dystopic movies ever, but for Wired, it’s even bigger, it’s part of the DNA. It's like Star Wars. When you play with that topic, [publications like] Entertainment Weekly or Variety can do it in a fantastic way, but the Wired perspective has to be completely different.

As a design process, we start with research about the essential elements that defined Blade Runner for Wired. We then choose a type, a colour palette, an aesthetic or, in this case, we’ll build actual sets with WIRED chief photographer Dan Winters. With Dan, we watched the movie over and over, hundreds of times in a week, to find the right elements to include in the sets he built for the photo shoot.

My favorite part of this, was that Dan (Winters, photographer) even built his own interpretation of a iconic Voight-Kampff machine. And as soon as Ryan Gosling walked in, he pointed at it and said to Dan “that’s for me, right?”

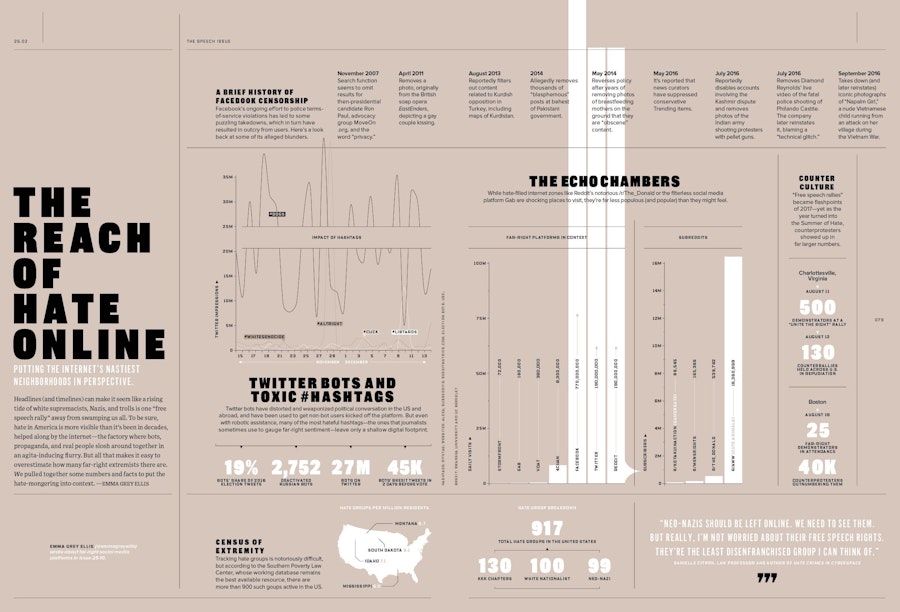

It's easy with science fiction or something that is so obviously Wired because I’m a nerd. But it was also very interesting to discover elements for our current issue, The Golden Age of Free Speech. Every research piece is a discovery. We are sometimes able to change stereotypes on what the Wired community is. It's a completely different generation. They are not the hackers of the '80s and '90s. They're the hackers of 2018.

Can you talk me through the process of putting together an issue of Wired with this in mind?

Let’s take, for example, our most recent issue on The Golden Age of Free Speech. For me, my process begins with a conversation with Nick [Thompson, Editor in Chief] and Maria [Streshinsky, Executive Editor.] We spoke about the issue’s theme, and they said, the idea of ‘free speech’ is something monumental. It’s the base of our democracy, and our technology, and recently, how it’s been used, how it’s changed… right now, it’s corrosive. There are some huge risks at stake. How can you defend the right to free speech — but also show that through the years, the idea of what free speech is, has changed. That’s what we wanted. To find a way to show the monumentality of this human right, but at the same time, acknowledge and show that the concept has changed.

For my department, research is key. We sit in on many editorial meetings, from the initial feature pitch meeting, up through meetings on how to take the story to the website, to our social media channels. We need to turn the aesthetic, photography, illustration, and typography of each story into something that is cohesive and consistent but related to the topic. What is our voice? Our perspective? What do we want to say? So when speaking about the ‘Golden Age of Free Speech’, the keywords were to say that this is the golden age of free speech, but there is something corrosive in it. Something is going wrong.

Being trained as a historian, taking from the past has given me the possibility to create a new, contemporary Wired.

I contacted the artist Sean Freeman. I spoke with him, and we talked about how conversation and speech, and we talked about time, and how a stone can age in time. A marble sculpture faces the weather, it faces acid rain, it starts corroding. That’s what ageing is, not the idea of “old” but that, as time as lapses, structures change their shape and form. The monument is still a monument, but time is changing it. It’s a very simple idea but I loved the concept.

With this issue, we also had another opportunity. Following Nick and Maria’s intentions, we realize that with a speech theme, we could have an issue where the typography could lead the design. We brought in the team at Commercial Type to develop a set of fonts and typefaces related to the tone of a single article, and create a series of openers based on statements.

We also decided on a specific colour palette to suggest that progression. The lineup of articles in the magazine leads to a final moment. If you see all the portraits, they are marginal. They are related to the content, but they are not the main voice. What you really see are words. It's a joy for a designer to play with type. I was so happy to have Commercial Type brought in for this project because I really love the way they paired a specific custom font to an article.

Design is part of the content itself. Not only does it define the frame, but it can suggest an emotion. It can involve you. It can provoke in you a specific reaction, or an emotional reaction.

Do you have many other international collaborators you're working with?

The great thing of working at Wired is that we have incredible designers that can create type and illustration, but we can also involve external contributors to make something really special. Over time, we’ve developed a ‘Friends of Wired’ club. For example, seeing a Christoph Neimann image in Wired is completely different than a Christoph Neimann in The New Yorker. Another great one is [photographer] Dan Winters, a very close friend of mine. We have the opportunity to ask our artists to develop a specific voice using their style, but still talking the Wired language.

And how does Dropbox play a role in all this?

Dropbox for us is a perfect place to share and archive content. In my Dropbox, there is an entire archive of personal research. We organise all our inspiration in creative folders. We love to be able to recall ideas, and having a place that can be organised, and at the same time give the possibility to share folders, and give us a space to continue conversations.

You mentioned before that you are a historian. How does that influence your process and the decisions you make?

There are no revolutions — everything is to evolve an idea.

I love to say that for me, working at Wired is like always working in “beta”. I don't feel there is a moment in which you say ‘I released something, now I can rest for a while.’ Even when we publish something there is always another conversation that goes on.

Nick Thompson joined Wired as our Editor in Chief just exactly one year ago. The first thing he said to me was, I really want my version of Wired to bring it back to it’s roots, to it’s original intentions. Not to mimic what was done in 1993, not a nostalgic approach, no vintage, no throw-back, but to analyze and understand the original reasons and intentions. So for me, being trained as a historian, taking from the past has given me the possibility to create a new, contemporary Wired.

All images supplied by Wired

Interview by Chris Barker