Storytelling in the digital age

“If you are a creative person, your currency is the way that you think,” explains Luke Acret, Creative Director (and Aussie expat) at Madefire, from a café in San Francisco’s Mission District. “That then applies to how you execute it.” It’s an easy enough mantra to understand, but disarmingly simple considering the career choices that have led him to take it as his own.

In the comic world, there's a saying that nothing truly dies. And in defiance of the purists, Madefire could be held personally responsible for future-proofing the industry. Founded in 2011 by Ben Wolstenholme, Eugene Walden, and artist Liam Sharp, their app-centric distribution model redefined how comic books are engaged with as a market and as a platform for emerging creatives to share their work.

Can you explain how Madefire operates as both a creative studio and technology company?

There are three departments within the company. The publishing side, the tech side, and the studio. I help lead the studio, where we create our own Intellectual Property (IP), plus world building and really dense backstories. The pedigree of the company is comics, but as we know comics are now turned into movies and filtered into mainstream culture so it's more like a ‘story factory’. Comics are just a great way to prove the concept of a great story.

On the tech side, Madefire invented something called a Motion Book, which (as the name suggests) is a comic book experienced with motion via an app. That’s all open-source technology, so anyone can go on and create their own comics through it.

Then there’s publishing which is a marketplace. Here, studios like Marvel, DC, Image, Dark Horse comics, can come to us to create motion books on their existing IP or host their catalogue of existing comics.

How is that curated?

The philosophy is always ‘creator first’. Madefire was started by creatives for creatives to have ownership of their own stories and a platform to share them. [For indie titles] we curate like a studio so the best stories will always be championed. If it's a great story and it's done well, we'll push it — we really stand behind that diversity. Flagship titles are curated by release or theme, and we try to strike a balance to keep the community and the industry self-fulfilling and fertile.

Can you talk me through the studio process from end-to-end? From the initial story pitch through to publishing.

The creative process behind a Motion Book is very similar to how a film treatment might proceed: Logline, outline, script (like a screenplay) treatment, concept art, storyboards, pencils, inks, colour, and then what we call ‘building’ where it’s taken into our Authoring Platform and made to include motion.

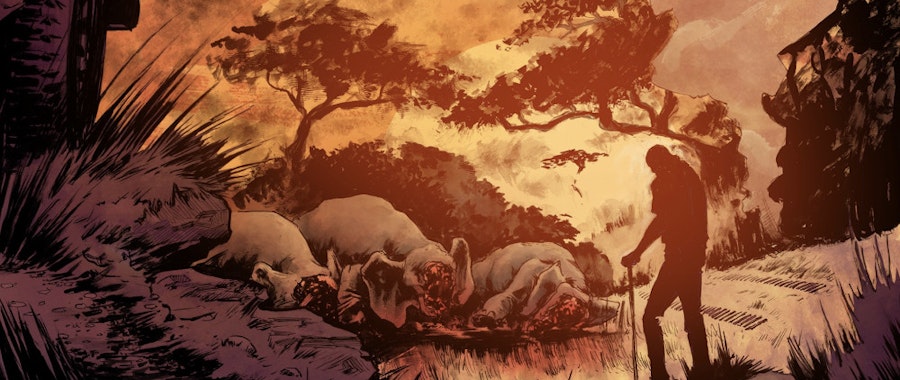

One of the most exciting things we're working on at the moment however is an interactive VR experience about a character named Mono. He's half man, half ape, ages in half the time as humans and leads a wild life as a former Queen’s assassin out for revenge. So that's an original IP titled ‘Mono — Blackwater’ created by our CEO Ben Wolstenholme, which is included in the SXSW ‘Virtual Cinema’ program.

For this, we partnered with Technicolor and wrote the story in the studio. Ben storyboarded it, and then I came in with the artist and production teams (plus an architectural team who specialised in the Classic Victorian era) to collaboratively define what the characters should look like, how the worlds should look, and the costumes. We treat it as if it were a film clip.

It's then a process of feedback between ourselves, Technicolor, MPC and their respective production teams in L.A and India where we’d all just jam ideas together. It’s a cinematic experience in story, but at a certain point you become a character within the experience and take over control of Mono and the graphic display to achieve different endings.

All the art department and modelling design is prepared by us, then handed off to Technicolour and placed inside the build. We did a motion capture shoot in L.A., and are constantly feeding back through with Technicolour and all the other moving parts—probably about 4-5 times a week.

And what about the additional elements, like the UI interactions and sound design — do you oversee that too?

Between myself and [Wolstenholme], we share those duties. So, in that respect again it's like a film shoot. We have a sound design studio, a motion-capture studio with sonic capture, plus we cast all the voice actors. This comes down to things like lighting, rigging, camera moves, UI design and game design. That's been a new thing for me.

And in this process, are you breaking any rules that you've taught yourself over the years?

The interesting thing for me has been transcending the technical limitations from film, which I'm very familiar with, to this VR world. For example, we have to consider things like frame-rates for motion sickness. A lot of times I’ll say ‘let’s do this with the design’ and someone will say ‘you can, but you’ll make someone throw up’ (laughs) so that’s been a learning curve. It’s just problem solving on the go.

When we’re creating Motion Books we often say that we don't want to be the worst video, we want to be the best reading experience, so that's the philosophy we try to stick to.

And what’s the feedback been from the comic industry?

The industry is a funny one because on one hand, you have a passionate community who believe comics should be in print only. We absolutely love that and consult with them regularly. But then you have this group of people who absolutely love [motion books] and they're just hungry for a great story. They really are. So, I think we've managed to do a pretty impressive thing. Yeah, their expectations are high, but there's certainly an appetite for it.

Do you think the major publishers will go 100% in on this new way of storytelling?

Already, every major publisher distributes digitally. Comic books will always have their place but I think they will continue to shift to the digital world as technology catches up with the imaginations of great storytellers. For example, we will soon be launching Madefire on Magic Leap to bring comics to mixed reality. I think when things start really being ingrained in people's heads and their lives and are perfectly immersive, it's going to be seamless. But it doesn’t have to be one or the other. Storytelling is storytelling.

How do you manage all the content that comes through from these studios and contributors across the globe?

When we're creating motion books, we're often pulling in world-class artists. What we typically like to do is pair a veteran writer with an up-and-coming artist or vice versa. So artists like Bill Sienkiewicz and Dave Gibbons, plus a host of up-and-coming creatives.

Our studio is in Berkeley but a lot of our people work remotely—places like Miami and Colorado, not to mention the production team in Bangladesh. And so a lot of the feedback loops are coming directly through Dropbox. It’s step orientated as well, so we start with pencils and then go into inks, colour, and then what we call ‘building’ which is essentially just assembling the motion book itself. But every step needs to be filed and put away for easy reference, which is where Dropbox comes in. We'll send work over to the relevant studio, and then we make sure we keep it on our end too—especially when it's storyboards and scripts where we're laying updated art or updated words. So, there is this back and forth approach where we're always working off the most recent file version.

So let’s talk about your background as an art director, and how you ended up in San Francisco?

I had a couple of really successful years in Sydney where I worked on Coca-Cola (‘Share a Coke’) and other great big clients, which enabled me the privilege to work wherever I wanted to around the world. I ended up moving to San Francisco to work at Pereira & O'Dell, which is a really great agency who produce Emmy Award-winning work. But after a while, I decided that I wanted to get out and work on numerous things at once and do things on my own terms, and eventually I landed at Madefire a little over a year ago.

The good thing about San Francisco is that you’ve got the tech industry, the agency industry, and the entertainment industry, and being on the West Coast really bridges those three together.

Having worked with technology companies, was it always the intent to push the possibilities of old-media formats?

Absolutely. I've always tried to structure my work to push boundaries because that's just what I like to do. It’s hard for me to try and just sell stuff to people. When brands start relationships with people and create work that they honestly enjoy, or even love, that’s when you are rewarded with sales. When branded content is done right and is entertaining, that’s the sweet spot for me and so that naturally is what led me to this execution-based world of giving things feeling, story and reason.

You also practice painting and photography. How important is that personal and tactile artistic expression to your day job?

When I first started painting a couple of years ago, it really helped me with my craft elsewhere. The repetition and creation of something that's all yours. You don't have to answer to anyone. There's no brief, no client, you don't make money off it, it has no responsibility attached to it. And like I was saying before, the reasons why you are a creative, what helps you feel good about the day-to-day, that's part of it as well. You're refilling, you're creating for the sake of creating.

When you’re creating for no one but yourself, what happens?

I feel like I definitely have an aesthetic, like an atmosphere or tone. There's a consistency across everything I do as an art director or a creative director. As for what happens? I feel like I'm experimenting a lot. A lot of it is a reflection of what I love and what I'm seeing out there. And I love that it's new to me and so I'm just trying to have fun with it.

I don't finish a lot of things but that's okay as well because I'm used to always trying to push it forward and try new things. At the end of a project I don't get to do that. I might be on some crazy deadline so I do what I have to. And so this is the protest, the rebellion against that.

There is a view out there that Australian and New Zealand creative industries are quite experimental compared to other markets. As someone who has worked across both A/NZ and US campaigns, where do you feel you have the most creative freedom?

[In the US] I feel like you can be experimental in a different way. It's that the market is so big here and a niche can still support an experimental idea because there's going to be enough people who are into it. You also kind of have to play it safe in some ways because you’re producing something that's going to be accepted by the masses.

When did you get interested in working in technology? Was it when you landed here or was it before that?

I think a lot of the work that I've always pitched or envisioned has been installation or digital-based. So I've always had that curiosity for technology, along with social ideas. The coolest thing to me is being able to have an effect on pop culture.

My philosophy on creativity is to be a generalist. A lot of people shun it, or maybe don't see the value and that's fine too. I'm not preaching that it's right, but I love when the currency is the thinking.

It comes back to trust. Creativity applied in a commercial sense is tricky at times. Clients often need to be able to pinpoint things in a service industry model, but it comes back to the currency of thinking and that is what should be bought and nurtured—that the idea and thinking is right first and foremost, so the trust can be brought to life in a way that does the thinking justice.

All images supplied by Luke Acret, Madefire.